Throughout history, the People’s Republic of China (PRC/China) has followed a policy of concealing capabilities and avoiding the limelight – sugarcoating defence capabilities – projecting them as humanitarian disaster relief aid. Beijing began thinking of building China into a “maritime great power” (MGP) as early as 2003 but its 2019 Defence White Paper (WP) reflects a more serious and concentrated pivot to furthering these capabilities. And it has been implemented in an aggressive manner through the People’s Liberation Army Navy’s (PLAN’s) current naval force at 350 ships and submarines, including 130+ major surface combatants. In contrast, the US Navy has just under 300 ships as of early 2020. But China’s ships are older, have not been as active as the US’, face manpower issues and have only begun to modernise and enhance maritime capabilities in the past few years.

The People’s Republic of China is extremely keen to become a “maritime great power” (MGP) by 2050 as that will complete its “great rejuvenation”. The four key approaches of China’s maritime strategy were stated by General Secretary Hu Jintao, on 8th November 2012, at the Eighteenth National Congress of the Communist Party of China: the “ability to exploit ocean resources”, a “developed maritime economy”, “preservation of the marine environment” and “resolute protection of maritime rights and interests”. This essay will demonstrate the last approach which has become visible as aggressive naval expansion in the Indian Ocean Region (IOR) with the following cases: the One Belt, One Road initiative (OBOR), Sri Lanka (Hambantota Port), Pakistan (Gwadar Port) and Djibouti (PLA Support Base).

Indian Ocean Region (IOR)

OBOR

The Chinese State Council WP of 27th October 2019 – China and the World in the New Era – traces the developmental path that China has taken today to become the second-most powerful nation in the world, with three broad parameters to measure a state’s authority being economy, military, and population. In section four of the WP – China Contributes to a Better World – under point no. 2 – Promoting world peace and development through our own development – it is stated that “The Belt and Road is an initiative for economic cooperation, not one for geopolitical or military alliance”. The PRC has always ‘looked one way, acted another’, and the BRI is the same thing but on the most spectacular, ambitious level ever seen by the world.

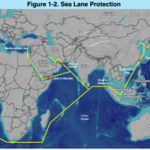

China’s ulterior motive is to create a network of ports that will aid its mission of achieving its national interests and strategic objectives, and although it will be of significant use for trade and economic development, these are not its only reasons. Its principal goal is to achieve naval connectivity in the Indian Ocean Region. The PRC has been successful on this account, as is evident by its ‘string of pearls’ strategy, wherein it is trying to encircle India’s southern tip by developing ports in multiple nations, from the Chinese mainland to the Indian subcontinent to Africa to the Middle East. And this where the BRI’s oceanic component, the 21st Century Maritime Silk Road, comes into the picture.

Sri Lanka

The PRC has a strong footing in the Indian Ocean Region due to its 99-year lease of Hambantota Port in Sri Lanka, a major boost for its maritime interests in the region, primarily because of its proximity to the Indian mainland. Regardless of whether China used the ‘debt-trap policy’ it does not take away from its national interests in India’s neighbourhood. At present, the PRC is adhering to economic and commercial interests, but it would be more prudent from an international security angle to maintain Hambantota Port in the commercial as well as naval sense, which would be a crucial point to control South Asia’s shipping routes.

These shipping lanes south of Sri Lanka are vital since they handle a third of the world’s global bulk shipping, as well as “90% of India’s trade by volume and almost all oil imports come via sea route”. In case of any sort of major conflict with India, China can very easily create a naval blockade from Hambantota Port to prevent oil imports from reaching the country.

Pakistan

Just like China has leased Sri Lanka’s Hambantota Port for commercial purposes, it has done the same with Pakistan’s Gwadar Port from 2015 onwards for 40 years. Along with the island port, Gwadar Port is also part of China’s ‘string of pearls’ strategy and is of vital interest as it allows its navy to potentially “monitor the SLOCs [sea lines of communication] in the Arabian Sea and the Persian Gulf, or at least gain access to critical port facilities”.

And if the reports of the PRC selling Liaoning, its “first and only aircraft-carrier” to Pakistan are true, it will seriously boost China’s naval capabilities in the IOR. The balance of power in the Indian Ocean Region will tip the scales in favour of China. But experts believe that China will only do something like this until it builds its own nuclear carrier as part of a battle-group, as the one that Pakistan might receive is an old Soviet vessel. The implication of this is that India as the other premier power in the IOR, may not have the time it expects to prepare a counter strategy. Indian naval power and a reworked strategy has only recently begun but there is still a long way to go to counter a true Chinese blue-water navy – a very real possibility in the near future given the accelerated capability to build its own aircraft carriers.

Djibouti

Apart from Sri Lanka and Pakistan, the People’s Republic of China extended its ‘string of pearls’ strategy to Africa in 2017 with the military base-cum port in Obeck, Djibouti that is officially known as the PLA Djibouti Support Base. Djibouti’s location is of immense geo-strategic importance as “approximately 11% of the world’s seaborne oil is transported through” the Bab el-Mandeb Strait, which links the Red Sea to the Gulf of Aden. It connects Europe to the Far East, and hence, various nations – the US, Japan, France, Italy, and Spain – have a military base in Djibouti even though it is one of the poorest nations in Africa.

For China, Obeck is of even greater significance given its vast oil investments in the African continent, with Angola being its third largest source of oil in 2018 – $24.9 billion – 10.4% of the total volume. Even though the PRC terms its military base as “a logistics facility for resupplying Chinese vessels on peacekeeping and humanitarian missions” because of the continuous instability in the region – including piracy – it is a full-fledged military base at the port in Obeck, and even conducted live-fire drills less than two months after making it operational.

These actions by China imply that it is extremely serious about protecting its oil investments in Africa as well as having a presence at the vital waterway connecting Europe to Asia and the Far East. One reason that has been put forward by practitioners of International Relations theory is that the PRC would have made Gwadar Port in Pakistan a military base as it has been developed as a deep-water port but did not do so due to its proximity with India.

Hospital Ship

The People’s Republic of China also uses certain techniques to deploy its navy faster, including using a naval vessel as a hospital ship, that is, Daishan Dao. This is just one well-known instance of the projection of Chinese naval power through semi-official military methods.

The Daishan Dao is a Type 920 hospital ship operated by the PLAN, and when it was launched in 2008, it completed the PRC’s “marine medical three-dimensional rescue equipment system” – “one ship, five boats, four machines”. This ‘three-dimensional rescue equipment system’ will aid in the rapid deployment of naval troops and assets as well as providing a crucial support role, ever since the PRC’s Defence White Paper – China’s National Defence in the New Era, published in July 2019, stated that

In line with the strategic requirements of near seas defense and far seas protection, the PLAN is speeding up the transition of its tasks from defense on the near seas to protection missions on the far seas, and improving its capabilities for strategic deterrence and counterattack, maritime maneuver [sic] operations, maritime joint operations, comprehensive defense, and integrated support, so as to build a strong and modernized naval force.

With these naval changes in China’s maritime policies, she is gradually evolving into a blue-water navy that can challenge any other country – including the US, currently the world’s most powerful navy.

Conclusion

With an 11,000-mile-long coastline and an ambition that exceeds anything the world appears to have seen thus far, China has rapidly emerged as a global naval force in multiple ways.

From a country beset by its own internal problems for centuries, it has succeeded in quietly but efficiently in redefining its role on the global stage. It has extended its naval reach in two ways: by accelerating its own naval ship-building capabilities and taking over ports in other countries of strategic geo-political importance. Among its key targets is India where it has adopted a ‘string of pearls’ approach to create a pincer movement on the high seas and flank the country with strategically-located ports in Sri Lanka and Pakistan. This is over and above its OBOR project that has surrounded India by land in the north. In addition, its growing investments in Africa are protected by Obeck Port in Djibouti, which also gives it control over shipping routes between Europe and the East.

Seen from a larger perspective, this expansionist policy may be a counter to the conflicts China faces closer home: it is engaged in territorial disputes over multiple islands with South Korea, Japan and Taiwan, and in frequent clashes with India as well as escalatory actions at the Line of Actual Control (LAC). In contrast, its presence in the Indian sub-continent and Africa is not conflagratory and has gone relatively unnoticed until it became too late for the US and India to counter fast enough.

China has also developed an extensive fishing fleet that is militarised and employs it in the South China Seas to exert influence and apprehension in other states. Having established itself as an economic, political, and cultural superpower, it is evident that China is now also a military force that the world cannot ignore by any means: the ‘Sleeping Dragon’ is awake and sailing the high seas.